William F. Jeffery,

Anthropology, University of Guam Mangilao, Guam 96915 USA

James D. Sellmann

Philosophy, University of Guam

Abstract

Keywords

Introduction

Environmental philosophy provides a gateway to develop a heuristic model to understand Yapese philosophy. Because Yapese philosophy is contained in oral traditions and various practices expressed in cultural rituals, forms of life, mores, habits, attitudes, beliefs, and thoughts, we will attempt to explicate Yapese philosophical values from rituals, beliefs, and especially fishing techniques, regarding the environment as they relate to sustainable food practices. We present the use of fishing techniques especially the tidal stone-wall fish weirs, called aech, as a classic example of a traditional sustainable fishing practice that should be rejuvenated. To study Yapese environmental philosophy is in large part to examine Yapese sustainable food practices. The aim of this short paper is to illustrate how Yapese maintain balance and harmony in acquiring their major staple fish, in association with their traditional ecological knowledge, and the spiritual world.

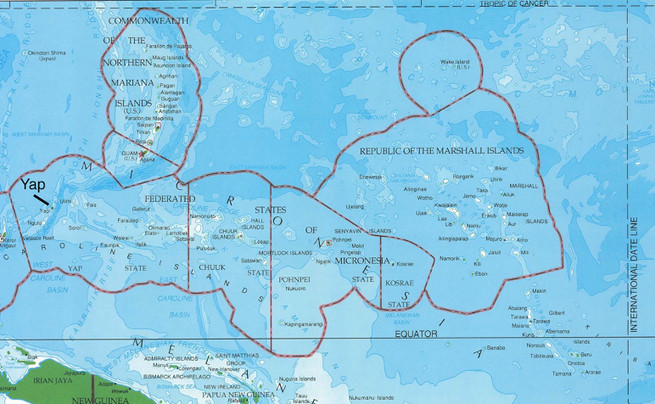

Location of Yap

In Western Micronesia, the arch of islands extending from just North of Indonesia to South of Japan, that is the Palau-Yap-Mariana island chains share important material goods and spiritual values. Through the spiritual (magical) power and natural resources of Yap, some of its shares values and trades goods moved Eastward through the Caroline atolls. Yap, or Waab, the traditional name, is located 840 km south-west of Guam, and 1,850 km east-south-east of Manila in the Philippines. It comprises four high volcanic islands, Maap, Rumung, Marbaa, and Gagil-Tomil. Combined, the islands are 24 km in length, north-south orientation, and 10km at its broadest, east-west, with a total land area of about 95 km2 and the highest elevation is 174 metres above sea level. The high islands are referred to as “Yap proper,” and together with seven small coralline islands and about 130 atolls that form the “Outer Islands,” they comprise Yap State, one of the four States of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), the other three states are Chuuk, Pohnpei and Kosrae (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Yap Locality Map (USDA-NRCS National Cartography & Geospatial Center, Pacific Basin Area, 1:20,000,000, Fort Worth Texas, 1999)

The population of Yap today is about 11,700, immediately after the WWII it was estimated to be 2,400 (Takeda 1999: 4), and before western contact the population was estimated to be in the range of 20,000 (Hunter-Anderson 1981) to 40,000 (Takeda 1999: 3). Yap is divided into ten municipalities and 134 village communities that are ranked into nine classes under three paramount chiefs from Gagil (Gachpar village), Tomil (Teb village), and Rull (Ngolog village). While there are complexities, variations and alliances that influence the ranking of many villages, what this established was a system of higher-class and lower-class villages, i.e. lower-class villagers that served the higher-class Yapese, and higher-class villages that supported lower-class villagers at certain times. Land, and the adjoining submerged land ‘sea-plots’ (and in some cases, beyond the reef flat) was owned by various family estates from within the village. Lower-class villagers could not own land, it was owned by a “landlord” from a higher-class village. These villagers sought access to food grown on the land and within the sea where they could be granted limited access to certain types of food and fish.

Traditional fishing methods

Fish were and continue to be a major source of protein for the Yapese and they developed a number of fishing techniques incorporating cultural and social practices (see Falanruw 1992; Hunter-Anderson 1983; Suriura 1939; Takeda 1999). The types of fishing practices include the use of various types of nets, line fishing, spear fishing, fish traps, and bamboo and stone weirs on the reef flat, using a bamboo raft or canoe. The various fishing practices can involve just a few men or a large number of men working together. Rites and magic are used in many practices, as when fishing outside the reef, and where villagers of the lower class are prohibited from fishing (Suriura 1939: 2; Pitmag 2008 personal communication). In some practices, men would gather beforehand in the faluw (men’s meeting house) at the times of the year that is conducive for catching the fish sought after. Group fishing provides for the sharing of the catch with participants and others in accordance with local customs, and if just a few people carry out the fishing, contributions, gifts, and tribute need to be made to others in accordance with local customs (Suriura 1939: 4).

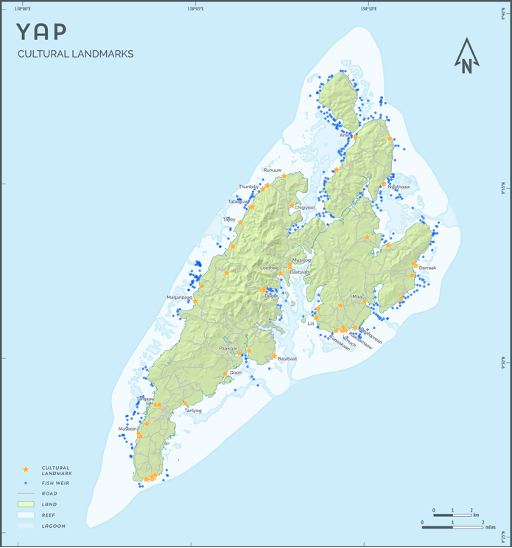

There were a number of traditional fishing methods used on the reef flat, and the most lasting example is the tidal stone-walled fish weirs (aech), of which it is estimated there were a total of 700-800, and they are all privately owned (Fig. 2). Yapese talk about the first seven aech being built by spirits. In an interview conducted by the Historic Preservation Office in 2002, a relative of an owner of an aech in Gagil, stated that this aech, being one of the initial seven was built by the ghost of a man named Mer many years before European contact, to “learn from and for catching fish…in a sustainable manner” (Jeffery and Pitmag 2010). Fish were caught at prescribed times, for a few days only, then the aech was opened up, “to let fish come and go, so as to make them feel at home” (James Lukan, personal communication, 2008). Those around seagrass beds caught rabbit fish, goat fish, emperor, or needle fish; while those built further out on the reef flat caught parrot fish, surgeon fish, trigger fish, giant trevally, barracuda, shark, grouper, stingray and turtle (Jeffery and Pitmag 2010:116-117) (Figs. 3 & 4).

Figure 2: Yap proper, the reef flat and location of about 450 aech (www.islands.fm/atlas)

Figure 3: The arrow-shaped aech adjacent to the coastline (Bill Jeffery)

Figure 4: An aech placed adjacent to a blue-hole, located away from the coastline (Bill Jeffery)

Results

It became clear during a 2008-2009 project that documented 432 aech, that the cultural landscape created by the aech and the associated cultural practices reflect a Yapese cultural identity. They highlight Yapese ingenuity and the harmonious, spiritual and sustainable relationship they had with the marine environment. The traditional council of chiefs, the Council of Pilung regard aech fishing as “sustainable fishing methods utilizing traditional ecological knowledge and practices.” (James Lukan, pers. comm., 2008). Today, they want to revive the use of the aech and the cultural practices, and to reduce the amount of fish taken by unsustainable, so-called modern, fishing practices.

Discussion

The subsistence life-style, as affluent as it was, keeps people in contact with the natural environment. As such Yapese describe their world in dynamic terms. Myths describe the islands as the remains of a primordial ancestor-giant, or other narratives describe how culture heroes fish the island out of the sea, or build the island on top of a submerged reef (Lessa, 1987, and Poignant 1967: 70-82) The hylozoistic world is full of creative energy, life power, spirit power, and spirits of the ancestors. Micronesian languages have their respective words, denoting a concept similar to the Polynesian mana (the life force permeating the universe and linking people to their ancestors and the land). In Yap the power is called kael. The CHamoru of the Mariana islands call it aniti. In Pohnpei and Chuuk it is called manaman. These terms denote the creative, life sustaining power of nature, consisting of a balance of two opposing yet interrelated energies, male/female, light/dark, right/left, life/death, and so on. The interpenetration of the two forces generate the creatures, plants, and things of the world. Depending on the amount of life power (kael or manaman) perceived or believed to be dwelling in the person, creature, plant, or thing establishes that person or thing in a hierarchical order, granting it a superior or inferior position. In human society the life power dictates the social, economic (land-ownership), and political power and status of the upper caste (chiefs, land-owners, navigators, warriors) over the commoners.

Conclusions

Yapese environmental philosophy contains an environmental ethic. Catching fish on the tidal reef flat employing the aech was implemented using traditional ecological knowledge of the whole marine environment, in association with traditional cultural practices, as shown to them by the spirit world. This contributed to achieving a sustainable food source in balance and harmony with the natural and the spiritual world. Conflict in this balance and harmony has come about through modern fishing techniques. In recent years, Marine Protected Areas have been declared at the village level, with State/Federal government support to incorporate traditional ecological knowledge in their management. This is an area of conservation/collaboration that is relatively new, and is now expanding across Oceania. In living on the edge between harmony and conflict, a person can move in either direction. There is an ethic to promote balance and harmony within the forces of nature and within human interactions with nature. This might be called the ideal Yapese environmental ethic. However, there is also what can be called the practical Yapese environmental ethic that is exhibited when people find the forces of nature or the human interaction with nature are out of sorts such that imbalance and conflict arise. This practical ethic pits humans against the forces of nature. It may well explain why some contemporary Yapese embrace an anthropocentric view of nature and the self-interest benefits of capitalism. When environmentally minded scientists or eco-tourists discover that Yapese property holders want to build hotels or oil refineries or develop a fishing industry despite the environmental degradation that will result, they may be mystified because they naively think that the only cultural value is harmony. The experience of conflict, however, gives credence to another value of domination and exploitation. Yapese living on the edge between harmony and conflict with nature are currently shaping and re-shaping their cultural ocean and landscape.

References

- Falanruw, Margie. 1992. “Traditional use of the marine environment on Yap.” Paper presented at the Science of Pacific Island Peoples Conference, Suva, Fiji.

- Hunter-Anderson, Rosalind. 1981. Yapese Stone Fish Traps. Asian Perspectives, 24(1): 81-90

- Jeffery, William, and William Pitmag. 2010. “The aech of Yap: A survey of sites and their histories.” Yap State Historic Preservation Office. Yap, Federated States of Micronesia.

- Lessa, William A. 1987. “Micronesian religions: an overview” includes Katharine Luomala, “Mythic Themes” in The Encyclopedia of Religion. Edited by Mircea Eliade. New York, New York: Macmillan Press.

- Poignant, Roslyn. 1967. Oceanic Mythology. London: Paul Hamlyn.

- Suriura, Kenichi. 1939. Fishing in Yap. Journal of Anthropology, 54(2): 1-12

- Takeda, Jun. 1999. “Fishing-gleaning activities on reef flats and/or reef margins in coral ecosystem in Yap, Federated States of Micronesia (FSM).” Manuscript with Yap Historic Preservation Office.

Personal Communications

- James Lukan. 2008. Former Yap State Historic Preservation Officer.

- William Pitmag. 2008. Former Survey Technician, Yap State Historic Preservation Office.